20th Oct 2020

Taking a Native American Studies class

Taking a Native American Studies class

When I took my first Native American Studies class during my freshman year of college, the lecture was filled with mostly white kids. I sat next to my white roommate, who, at one point in class when my tribe was mentioned, told me to raise my hand and “say something”.

“What the hell am I supposed to say?” I asked her.

“Just say that’s your tribe or something, I don’t know,” she replied shaking her head as if I’d just disappointed her.

While this didn’t happen often, it made me realize that taking Native American Studies (NAS) classes, would mean something completely different for me than it would for my white and non-Native classmates.

You see, Native Studies is essentially the study of me, of my people, of our history and our culture. For one, it will be the first time that I, as a student, will fully learn the extent of colonization and violence against Native people. It will also be the first time that I, as a Native woman, will see the connections between that violence and the many issues facing my community today.

For my non-Native classmates, this history surprises them. It shocks them when they realize the issues they see among Native communities are not simply choices or a lack of discipline or focus but are in fact real impacts of colonial history.

Henry Charpentier was in my tribal sovereignty class in 2019, his first NAS class, at the recommendation of another political science student. Henry grew up in Billings, Montana, a town close to both the Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations. Now, a first-year law student, he got his bachelor’s in Political Science, History, and a certification in Native American Studies from the University of Montana.

Before taking the class, he thought he’d known a good amount about Native people and their culture/history due to his father’s work at St. Labre Indian School on the Northern Cheyenne reservation.

“I knew [tribes] were distinct cultures and that there was some pretty horrendous treatment by the hands of settlers,” he said. “I overlooked a lot of negative factors surrounding white people’s contact with Native Americans. I just chalked it up to: it was bad, but it was good now, there might be some animosity but we’re largely too far removed from it to make much of a difference. I certainly didn’t grasp the full significance of the history.”

The tribal sovereignty class at the University of Montana examines the “evolution of tribal governments from a historical and political perspective.” In addition to this class, Henry took other NAS courses that led to his certification.

“It really changed my perspective of the United States and U.S. history,” he said. “I was really shocked to find out just how relevant all these issues are today that have direct causes from history and the past.”

As a result of his first NAS class, Henry felt a responsibility to do what he can to help Native communities today. To take a class not only focused on Native history but also with Native students in the classroom as well as a first for him and something he’d always hoped for in his education: diversity.

While tokenism is for another discussion, it still exists heavily in NAS classes with Native students in them. Just as my white roommate expected me to speak when my tribe was mentioned, we as Native students must relive our own personal trauma and that of our communities by sharing real-life examples of it to benefit the education of our non-Native peers.

For Henry, hearing personal stories and experiences brought to light issues he wouldn’t have heard otherwise. In just his tribal sovereignty class he was informed of all the issues and setbacks of serving on a tribal council in rural Montana. Thanks to a former tribal councilman who also took the class.

In another Native studies class, we watched a documentary called The Canary Effect about contemporary Native American issues. The hour-long film covered more well-known issues such as boarding schools, suicide, and the effects of alcohol and substance abuse. However, it also exposed hidden history that is seldom talked about like forced sterilization, mass adoption of Native children, and historical trauma.

The first time I watched this film, I had to leave the classroom to compose myself. I went to the bathroom and just wept. The second time I watched it in another class with the same professor, a friend of mine got up and left the room during the same portion of the video. He later told me he left because he also got emotional.

The scene featured two Lakota parents talking about the suicides they see among the children and teens of their community. Breaking up the interview were stats about suicide rates in Indian country and stories about children as young as 10 years old creating and carrying out suicide pacts on reservations.

“You see a lot of kids running around with rope burns around their necks from trying to hang themselves,” the woman said, her voice getting tighter and her eyes watering.

That’s when I left. I left because I was reminded of a young man I went to school with. We went to the Boys and Girls club in our agency together and I always remembered him and his little brother. They were just like, funny little smartasses.

Buster grew up to be a bull rider and was about to have a son when he took his life. Nobody saw it coming. No one knew how he felt underneath his humor but we sure felt it after he was gone.

I hadn’t thought about him in a long time until I saw that video and I was thrust back into that pain everyone had right after he’d done it.

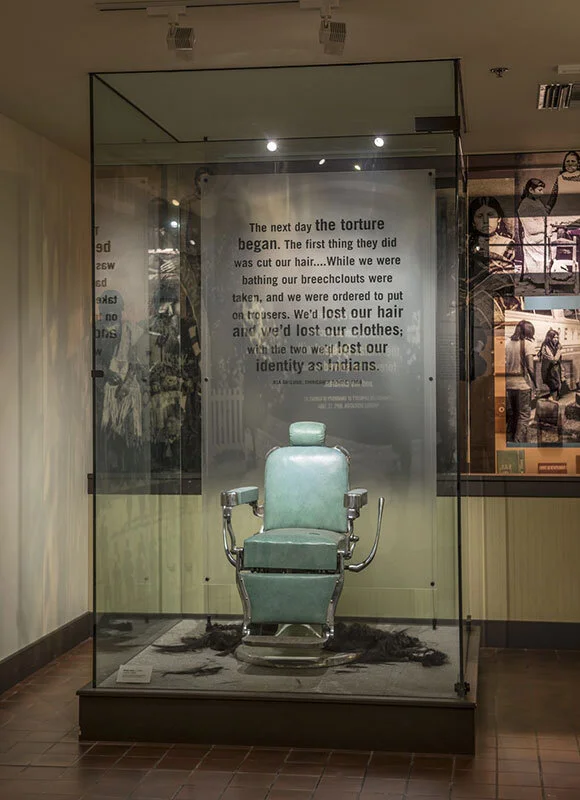

After my reaction the first time, I called my mom and told her what happened and how it affected me. Never before had I been so overwhelmed with emotion that I needed to leave a room. My mom told me that she’d had a similar experience when she went to the Remembering Our Boarding School Days exhibit at the Heard Museum almost 20 years ago.

She said the exhibit had been set up to mirror the boarding school experience. When you entered, you were faced with a huge photo of a train engine, so big it was almost overwhelming.

As you walked further along through the exhibit you came to a blue barber’s chair inside a showcase. On the floor along the base of the chair were piles of dark black hair, some loose and haphazard, and others in braids still.

Across from the barber’s chair was a collage of photos depicting Indian children. One photo was of Lakota children waiting to go to school. A placard told readers that the children ranged from 3 to 6 years old, the same age as my brother and I at the time.

That’s when my mother lost it and left the exhibit.

Lakota Children waiting to go to boarding school

“Here were these little children that were the same as my children. They all still had their Indian clothes on and their hair. They had no clue what was waiting for them,” she said, her voice straining as tears came to her eyes, even 20 years later. “It hit me because here were these children that still needed their parents. My children still needed me. I almost felt that pain as a parent to send my children away like that. It was just this helplessness.”

My great-great-grandfather had gone to boarding school as a small child. He didn’t come out until he was 21 years old and would never really talk about his experience.

Those children could have been my brother and I, had we been born then. Or even scarier, one of those children could literally have been my great-grandfather. For a lot of Native people today, those children are their parents and grandparents who carry the scars of those schools and pass them onto their children.

The effects of this trauma are still present in Native communities, they have become realities in our daily life, just more and more things we must live through as Native people, and we do live through them, they don’t stay in the classroom. When we go home for holidays, when we go out with our friends, when we laugh at our abuse stories, the trauma is there. When we cry about those we’ve lost, those we loved, and those we miss so much, the trauma is there.

To my white classmates, the high suicide rates on reservations are sad. They find the statistics for Missing and Murdered Indigenous People shocking. However, to me, they are more than just stats; they have names. They have faces. They have families. They were empty seats next to me in high school classrooms. They were Buster Birdinground and Ashley Loring, Selena Not Afraid, and Jermain Charlo.

Furthering the burden of knowledge, oftentimes our own communities aren’t aware of some of the brutal colonial history, and we as Native students are tasked with retelling the information we learn in a classroom to our friends and relatives back home. Not only do we have to relive the trauma of our ancestors and communities in the classroom but we must also relive that trauma by teaching others.

Teaching our communities what we learn when we go away is ironically the reason many Indian parents sent their children to a boarding school, to move the community forward. That is one of our responsibilities as members of our nations, we must move our people into the future in a good way and that means sharing with them the knowledge we’ve acquired so that we all can become better.

The ability to learn about ourselves is so important and is often taken from us by white schools, they don’t teach us our ways and we aren’t told fully what happened to our people. If you don’t know what it’s taken to get here, how can you ever hope to move on and be whole again? Community healing is so necessary for Indigenous communities and the brunt of that healing is put on the shoulders of educated people, to show everybody else how to move forward. Something my white peers aren’t faced with.

This poses an issue because our white classmates take the class as students should, purely for the furthering of one’s education. Once the class is over, however, while they may be shocked by the information they’d learned, they can check-out and return to their normal lives, tapping into their newly acquired knowledge when it’s convenient for them.

Of course, in any class that deals with heavy information that affects the lives of millions, there’s always going to be some pull at your heartstrings no matter who you are. To me, however, the difference of impact from student to student lies in how they are connected to the information presented.

For me and my Native classmates, these issues are not anonymous, they are not abstract or distant, they are personal. Things like colonization, poverty, and language loss impact our lives every day. They are not just a history or diversity credit. We are made to face the knowledge that our people, our grandparents, great-grandparents had and are still going through that colonial trauma. This knowledge is very personal for us. In many ways, it is us and we cannot walk away from it so easily.

-Jordynn Paz